Navigating the storm: Shipping and its net-zero challenge

The shipping industry is facing a monumental challenge from climate change.

Not only is the sector one of the most significant carbon emitters and under increasing pressure to decarbonize, but it’s also at the frontline of the changing climate.

Rising sea levels, disrupted weather patterns and more volatile weather events significantly impact shipping routes, infrastructure, and the industry’s profitability.

Making not just a moral case but also a financial one for the industry to reduce emissions and safeguard a more sustainable future.

Shipping is integral to the global economy and helps drive prosperity and poverty reduction across the planet.

Marine transport delivers 80% of the world’s trade, and demand is increasing yearly.

In 2021, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimated that shipments grew by 3.2% to reach 11 billion tons.

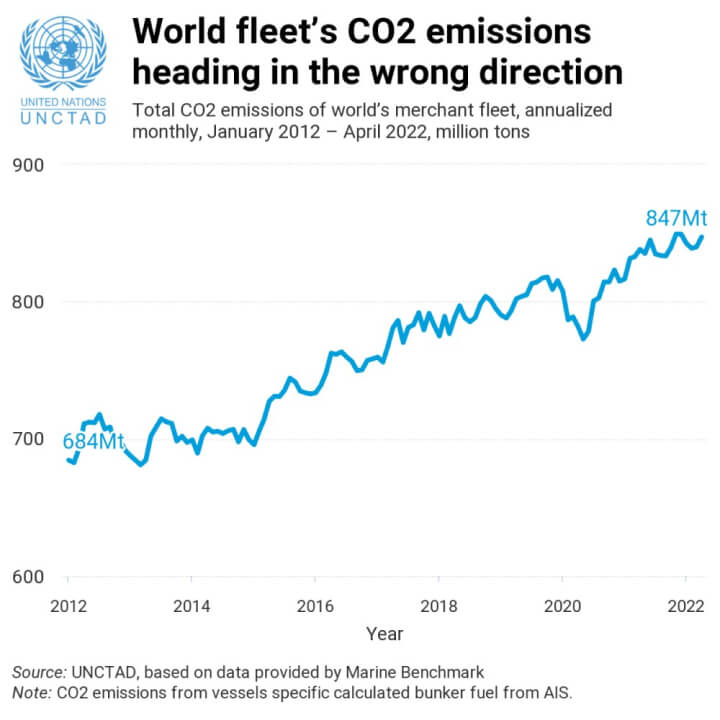

The challenge for the shipping industry is as it grows, the greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) from the world’s maritime fleet are also going up.

Between 2020 and 2021, UNCTAD estimated that GHGs increased by 4.7%, mostly coming from container ships, dry bulk carriers and general cargo vessels. GHGs are rising, and innovation and regulation are not responding quickly enough.

Change at a national level

There is momentum for change gathering at a national level.

20 countries have signed the Clydebank Declaration for green shipping corridors that supports the establishment of zero-emission maritime routes between two or more ports.

At the end of March, the EU agreed to the world’s first green shipping fuels law. Ships will be required to use more sustainable fuels, and at least 2% of the bloc’s shipping fuels will need to come from e-fuels derived from renewable electricity by 2034 at the latest.

The UK has also launched the UK Shipping Office for Reducing Emissions (UK SHORE), and it recently announced an investment of £77 million to launch a zero-emission vessel from a UK port by 2025.

The US and Norway organised the Green Shipping Challenge at COP27, encouraging governments, ports and shipping companies to commit to a green transition. And earlier this year, South Korea published its roadmap to decarbonise its shipping industry by 2050.

This is a start, but the industry must move faster to make meaningful progress on lowering GHGs by 2030 and getting anywhere close to net-zero by 2050. Decarbonising the global sailing fleet of approximately 100,000 ships represents a monumental task requiring more energy-efficient ships and a revolution in the entire fuel supply chain.

As we’ll explore in more detail in this article, there needs to be a dramatic acceleration in using alternative, low-carbon fuels – like those from green hydrogen and a significant increase in investment in energy-efficient shipping technologies.

Ultimately, the market will give the shipping industry the momentum it needs. Increasingly businesses will be using maritime transport to move the resources and components to fulfil their net-zero ambitions. Consequently, an essential link in a net-zero global supply chain still emitting significant GHGs will be unacceptable to most industries.

In the longer term, the market will reward shipping companies and ports that champion a more sustainable approach now.

Shipping’s climate impact

Shipping represents 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs).

That may sound relatively small, but if the maritime freight industry was a country, it would comfortably be a top 10 GHG emitter.

According to the shipping regulator, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), emissions from maritime transport are set to increase by up to 50% by 2050 unless significant restrictions and alternative fuels are not widely adopted.

Currently, approximately 99% of the energy demand from the international shipping sector is met by fossil fuels, with fuel oil and marine gas oil (MGO) comprising as much as 95% of the total demand.

Despite the urgency of the challenge that IMO has set out, it’s still only committed to a 50% reduction of 2008 emission levels by 2050. That’s regardless of pressure from several of its own member states at its last committee meeting in December.

The hopeful news is that the next time it meets in July, the expectation is that the IMO will set an official 100% net zero target by 2050. That also may include more stringent economic measures like a carbon levy system, an effective way of implementing the ‘polluter pays principle’ in the shipping industry. We’re already seeing some countries pricing those changes into their own net-zero shipping strategies.

The challenge for the shipping industry is clear, but the roadmap to net-zero by 2050 is less so.

The two most powerful levers are alternative and sustainable marine fuels and more innovative design and energy efficiency in the global fleet. The issue is that both need more explicit regulation and significant investment.

The Global Financial Markets Association (GFMA) estimates that shipping will need at least $2.4 trillion in funding to reach net-zero by 2050, and $1.7T of that will need to go into developing sustainable marine fuel.

How close are we to clean marine fuel?

Developing alternative and sustainable marine fuels is the most important factor in the shipping industry reaching net-zero by 2050, but the slow progress in adoption and innovation is a concern.

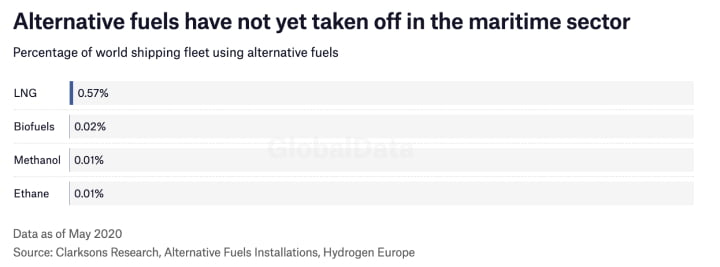

As you can see from the figure below, oil-based products still constitute more than 99% of the total energy for international shipping.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), to get on track to net-zero, alternative fuels, including biofuels, hydrogen, ammonia, methanol and electricity, must represent 15% of shipping’s total energy demand by 2030.

That’s a dramatic shift and will need clear regulation, government support, industry cooperation and innovation to become a reality.

The IEA estimate that half of the low-carbon fuel by 2030 can be biofuels; the significant advantage is that they’re ‘drop-in’ alternatives, and existing vessels can use them. But biofuels are still only a stopgap, and as we’ve discussed previously, they have their own sustainability challenges to overcome.

There’s also a demand for new ships powered by liquefied natural gas (LNG), which, although significantly cleaner than traditional bunker fuels, is more of a sticking plaster for the shipping industry than a long-term solution.

The alternative fuels that will make the biggest impact on shipping’s net zero targets will be green hydrogen or those based on green hydrogen, like clean ammonia and e-methanol.

However, there still needs to be a consensus on which alternative fuel the shipping industry should pursue, and they all come with their own challenges.

The green hydrogen revolution

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that green hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels will represent 60% of the energy mix for shipping by 2050, but that needs a huge shift in direction and investment to realise.

Green hydrogen is produced by electrolysis, which splits water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. Since electrolysis does not give off carbon dioxide as a by-product, green hydrogen is the only form of hydrogen with a virtually carbon-free production process. It’s even cleaner if the electrolysis uses electricity generated by renewable energy.

Some have heralded green hydrogen as the panacea for sustainable marine fuel. However, it’s still prohibitively expensive to produce at scale, and even though it’s relatively easy to retrofit hydrogen fuel cells to existing ships, the storage takes up significant space.

Hydrogen is also highly flammable, an evident safety concern, and much less energy dense than other alternatives, meaning ships would have to rely on a currently non-existent green hydrogen infrastructure to refuel more often.

Green hydrogen-derived fuels – specifically, clean ammonia and e-methanol – are also emerging as potential alternative shipping fuels.

Two of the biggest shipping companies globally – A.P. Moller – Maersk and CMA CGM – have ordered multiple methanol-powered ships and are investing in potential methanol bunkering at some global ports.

The world’s first ammonia-ready ship was also delivered last year to Greek shipowner AVIN INTERNATIONAL L.T.D.

The challenges for both potential energy sources are their current cost and a shortage of green hydrogen feedstock. Clean ammonia also has an image problem, with some ports reluctant to bunker the fuel because of toxicity concerns. A pilot testing programme for ammonia bunkering is set to begin at the Port of Singapore at the end of 2023.

Whichever alternative marine fuel gains the greatest momentum, bunkering infrastructure and the development of zero-emission vessels must also go hand in hand. That work must accelerate now if the industry has any hope of reaching net-zero by 2050.

Zero-emission vessels

Alternative fuels are just one large part of the puzzle. Zero-emission vessels are another significant piece.

The shipbuilding industry faces an urgent challenge as innovation could be stymied by long vessel lifetimes and slow stock turnover. Given the typical 25-year life of new oceangoing ships, if the industry is to reach net zero, there must be thousands of zero-emission ships in the water by 2030.

UNCTAD estimates the average age of the global fleet is 21.9 years, which is another environmental concern as older ships tend to pollute more.

The organisation also suggests that the ageing fleet is partly due to shipowners’ uncertainty about regulation and which alternative fuels to invest in.

The global commercial fleet grew by less than 3% in 2021 – the second lowest rate since 2005.

However, there’s some progress being made on cleaner ship technology.

The research organisation, Global Maritime Forum, analysed more than 200 zero-emission pilots and demonstration projects in 2022, up from 106 in 2021. They found that 45 projects are focusing on hydrogen, another 40 on ammonia technologies; 30 are battery-powered vessels, and about 25 are methanol projects.

Orders for new ships are also showing a slow trend towards alternative fuels. However, LNG is still the preferred option for shipowners waiting for hydrogen, ammonia or methanol to become less expensive and more scalable.

275 alternative-fuelled ships were ordered in 2022, with over 80% of them being powered by LNG.

Methanol was the second most popular alternative fuel choice, with 35 ships ordered, and there were orders for 18 ships capable of running on hydrogen fuel.

It demonstrates the evident lack of regulation and direction that shipping companies are ordering new vessels ready for alternative fuels without the required infrastructure or fuel supply.

Morten Bo Christiansen, head of decarbonisation at A.P. Moller – Maersk, told CNBC last year that they had partly ordered their latest alternative fuel vessels to signal demand so that alternative fuel production would ramp up.

Turning the oil tanker around

The difficulties of turning an oil tanker around symbolise the many challenges associated with the path to net zero for all industries. But just as many other sectors have adapted rapidly, the shipping industry needs to catch up.

Even now, as it slowly heads in the right direction, regulators still need to offer much more clarity and guidance about the best way forward.

As we’ve discussed, the industry is primed to make the changes it needs to, and the market is encouraging a more progressive approach, but the clock is ticking, and time is running out.