Are we beginning a new age of copper?

Should copper bulls be celebrating?

Copper is one of the oldest metals mined and used by humans, but in many ways, it’s never been more relevant than in 2024. It’s crucial to the clean energy transition, vital to AI and the burgeoning data centres the technology needs, and a key economic bellwether that gives us a good picture of where the global economy is heading.

And things are looking up, at least for copper.

The metal has been in a fairly persistent uptrend since early February after trading sideways for most of the last two years. Despite the bearish scenario since 2022—high-interest rates, weak manufacturing data, and the slowdown in China—copper has done well to maintain its price. However, in the last two months, it has joined other key commodities in looking more bullish.

The price has been supported by some better global economic data and some renewed (perhaps hopeful!) optimism about demand, alongside supply concerns from production downgrades at several copper mines. The price now appears to reflect the expectation of a supply deficit of copper concentrate in 2024 and beyond.

It was only last year that some miners and analysts predicted a “train wreck” of a copper supply crunch and significant price rises as those supply issues met green demand.

Although that situation has yet to materialise, are we beginning to see the next real growth phase for copper, or is the current price action as much to do with financial flows and increased speculation as fundamentally driven?

Regardless of what’s driving the recent price rises, copper bulls should not be celebrating just yet.

What’s driving the price of copper?

‘Dr Copper’ has an uncanny ability to (at best) predict (or at worst, give us a spot assessment of) the health of the global economy.

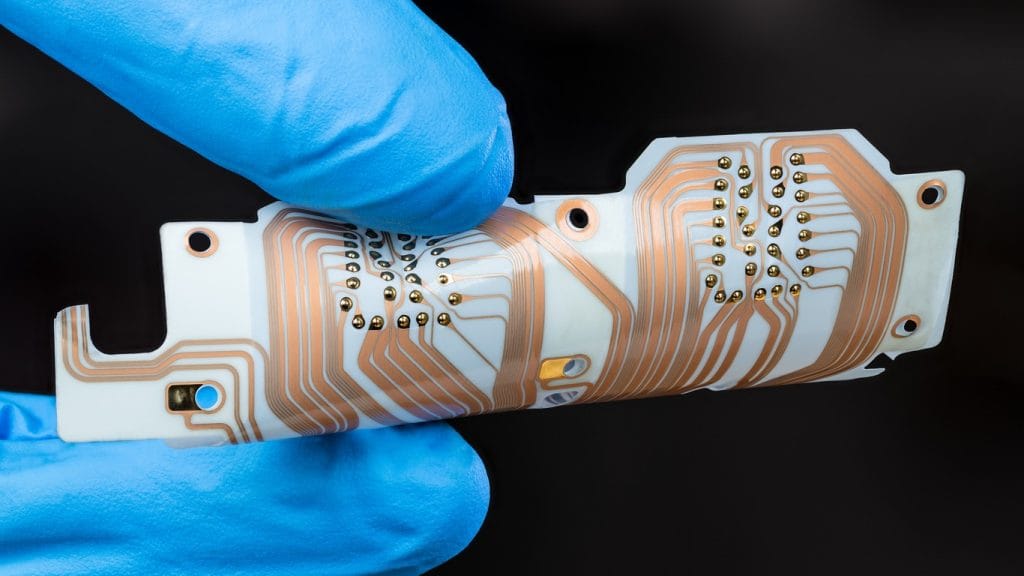

This is due to its widespread use across construction, automotive, electronics, manufacturing, and, more recently, clean energy components, data centres and AI hardware.

Higher copper prices generally mean high demand and a positive global economic outlook. However, this time appears to be different. Despite some positivity around recent global manufacturing data, several indicators suggest that current copper demand remains soft in key markets, predominantly China.

The implication is that consumers are resistant to purchasing at these high prices, which is often a precursor to a price correction or normalisation. It’s hard not to be bullish about the long-term price of copper, considering its key role in so many crucial sectors, but what’s becoming clear is that this current rally isn’t entirely being driven by strong demand in the near term.

The physical copper market doesn’t appear supportive of the current prices, but that does not mean the price will inevitably come down in the near term—speculators and momentum traders, or macro influences like inflation and the USD, can just as easily drive price action away from any fundamentally justified “fair value” or push it up in advance of an improvement in supply-demand prospects.

Near-record longs

The current price is supported by supply headwinds and near-record longs from speculators. Therefore, the next question is whether this is a fundamental or financial rally or a blend of both. Exactly how much of the recent rally is due to speculators?

Unfortunately, it’s almost impossible to quantify. We just don’t know how much the current rally is due to the supply/demand dynamics versus the volume of financial flows we’ve seen enter the copper market. As much as physical supply chain players, such as miners and manufacturers, would want a clear answer, the only useful response is that the current price is representative of the total package of what’s on offer. The financial flows and the fundamentals cannot be disentangled.

The demand story

What we can be certain about is that spot market Chinese demand isn’t pushing the copper price higher.

As the world’s largest producer and consumer of refined copper, China has an outsized impact on global copper markets. The market sentiment in China is normally at the forefront of any conversation about price, but not right now. Current market conditions in the Chinese copper market are soft. The spot premium for physical metal in bonded warehouses in China is currently around flat and the lowest in several years. This means that there are few buyers who want to buy units and pay duty on them before importing inland. Also, the spot premium for copper that has already been cleared by customs is now negative, meaning a consumer can purchase physical units cheaper than the nearby futures contract.

The slump in demand has primarily been driven by the struggling Chinese property market, which, according to some estimates, accounts for 20% of overall Chinese copper demand.

Some of the initial optimism from copper bulls came from the hope that the Chinese government would back a stimulus package and better than expected PMI data in March, combined with stronger than expected Q1 GDP growth (+5.3% YoY vs +4.8% expected). However, the demand data is what everyone is watching, and that’s currently showing no signs of improvement in the near term, especially considering the global picture and the FED managing expectations around interest rate cuts in 2024.

The slump in demand has primarily been driven by the struggling Chinese property market, which, according to some estimates, accounts for 20% of overall Chinese copper demand.

Copper demand will be a much longer-term narrative—which we’ll explore below—but for now, the tightening supply outlook is dominating, and China also has a significant role to play in that story.

The copper supply squeeze

Copper mining and refining is a global industry. The ore is predominately found in North and South America, and some of the biggest mines are in Chile, Peru and Mexico.

Once mined, copper is either exported as ore or processed into ‘concentrate’, which contains up to 30% copper. Most exports go to Asia, particularly China, Japan, and South Korea, as well as Europe and the U.S.

There have been ongoing issues with the global supply of copper ore and concentrate for several years. Supply growth has been sluggish: mined output globally in 2022 was 21.8 million tons, according to the International Copper Study Group, rising only 1 million tons over the previous three years.

There’s little indication of that accelerating in the short term.

Research from Goldman Sachs suggests that regulatory approvals for new copper mines are on a downward trend, having fallen to the lowest level in 15 years. This is particularly concerning, given that mines can take anywhere between 10 and 20 years to approve and develop. The bank estimates the industry needs to spend $150 billion over the next decade to address a projected 8-million-ton annual supply shortfall. On that basis, we need much higher prices to stimulate the capital allocation miners need to bring more capacity online.

There have been ongoing issues with the global supply of copper ore and concentrate for several years

This wouldn’t be such a problem if existing mines weren’t also ageing, meaning there’s a reduction in the quality of the mined ore. The average age of the world’s ten biggest mines is 64, which means miners must dig deeper for ores of ever-lower quality.

Opposition to copper mining

Copper mining projects are also facing some serious geopolitical, regulatory, social and environmental obstacles. In Peru, protests at the country’s major Las Bambas mine have led to 600 days of stoppages since 2016. In December, Panama’s Supreme Court ruled that the government should shut down one of the world’s largest copper mines — Cobre Panamá, operated by Canadian mining company First Quantum Minerals — following fierce public protests. In Chile, Codelco —the state-owned mining company and the world’s largest copper producer—has been beset by project overruns and spiralling costs at its Chuquicamata mine, as the miner is in the process of building an underground section to the century-old open pit mine.

These examples and others mean that the short and long-term production outlook is tightening. A copper concentrates market deficit is expected this year, with that supply gap widening further into the decade. There is just no feasible way supply can keep pace with increasing demand in the medium term.

Copper mining projects are also facing some serious geopolitical, regulatory, social and environmental obstacles.

Chinese smelters

If the squeeze on the mined copper supply set the foundations for a price rally, then it was the Chinese smelters who really set the bulls running. China is not only the leading importer of refined copper, but it’s also the largest copper producer – almost half of the largest smelters globally are operating in the country.

In March, those smelters decided to act together in response to the shortage of raw materials; they agreed to joint production cuts across the industry. The decision came as their fees to process copper concentrate on the spot market dropped to the lowest in more than a decade.

Chinese smelters have been rapidly expanding their capacity over the past year to prepare for an expected surge in copper demand from the green energy transition. The shutdown at the Cobre Panamá mine, in particular, has caught them off-guard, as much of that copper was bound for Chinese smelters.

There still doesn’t seem to be a uniform agreement on what these smelting cuts mean across the board. Early reports suggested that each smelter will make its own decision on the scale of cuts.

One number to watch is the level of inventories on the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE), which have already surged to levels not seen since 2019. The pace of this inventory build-up is a useful measure of the effectiveness of the pledged smelter cuts and what that means for supply.

Entering the ‘Copper Age’

It seems sensible to be cautious about this copper price rally in the near term. Tightening supply has been the catalyst, triggering a huge volume of financial flows that have combined to sustain higher prices. The bears might justifiably suggest that if there’s more positive news from mines in Central and South America, the smelting cuts take effect, and money managers start to look elsewhere. Then, without the emergence of real demand in the coming months, the price really does begin to look overbought.

However, the long-term prospects for copper demand are much more positive. It’s no overstatement to suggest that we’re entering the ‘copper age’. Due to its versatility and conductivity, copper is already playing a vital role in many of the world’s most important technologies, from the clean energy transition to AI hardware and data centres. That demand will only increase from here.

Clean energy components

Copper is called the “king of green metals” for a reason. It’s critical in multiple green energy applications, from batteries to solar PV technologies, wind turbines and electric vehicles (EVs) as well as broader global electrification activities. For example, a three-megawatt (MW) wind turbine contains up to 4.7 tonnes of copper, and an electric vehicle (EV) needs almost four times more metal than an internal combustion engine.

Projections suggest that annual global copper demand could almost double in the next ten years due to the demand from the clean energy sector. The real challenge will be meeting that demand with the supply deficits we’ve already mentioned. Copper supply issues could—in a very real sense—derail the world’s Net Zero ambitions.

Copper is called the “king of green metals” for a reason.

AI

Copper is also playing an important role in underpinning the emergence of AI technology, which is extremely data—and electricity-intensive. We’re seeing extraordinary data centre growth globally, which in turn means greater power consumption. The whole AI ecosystem needs copper to function, not just the data centre itself but also the connections to the power grid and any storage or backup generator capacity. Combining the explosion of AI demand with the proliferation of general data usage and streaming services, data centres should provide copper demand for decades to come.

In the near term, we expect more volatility in the copper price as we navigate this new market phase. Tight supply conditions and speculative financial flows make a compelling case for a bullish outlook, but we’ve seen how quickly the macro data can change, and without more positive demand numbers from China, the price could well fall just as quickly.

However, the long-term view presents a compelling case for copper. The greatest challenge will be resolving the constrained supply chain to meet the world’s ever-growing appetite for the metal. It’s no exaggeration to say that the supply and demand dynamics of copper will shape the future of the global economy.

It may be an ancient metal, but copper’s never been more relevant.