What does El Niño mean for the supply of global food?

The early signs of El Niño are here, but is a fragile global economy ready?

According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center, the chance of El Niño developing this summer is now over 90%.

The NOAA suggest that there’s a greater than 50/50 chance it could be a “strong event” and over an 80% chance it’ll be “stronger than moderate”.

The temperature of the equatorial Pacific Ocean, particularly off the coast of Peru, has begun to rise, and the trade winds have started to ease, both strong indicators of the transition to El Niño.

The Triple-dip

El Niño’s arrival follows an incredibly rare three consecutive seasons of La Niña, which brings cooler waters to the eastern Pacific and colder, wetter conditions.

That ‘triple-dip’ has taken place just twice before on record.

But now El Niño appears to be in the ascendency, and it’s highly likely it will continue as the world’s dominant climate pattern through the northern hemisphere winter of 2023/24.

So, the key questions are:

- How strong will El Niño be this season?

- What impact will there be on global food markets, already tight after a period of geopolitical tension and three years of La Niña?

It’s early days, and El Niño varies by intensity and geography, with no two episodes the same. However, previously, the phenomenon has had a widespread impact on the world’s weather, often bringing cooler, wetter conditions to the Southern states of the U.S. and drought to countries in the western Pacific, such as Indonesia and Australia.

The last strong El Niño in 2015/16 saw the highest-ever recorded global temperatures, and we’ll examine below why there’s a high possibility of a new record this time.

What’s in no doubt is that a strong event could add even further supply disruption to already volatile global food markets.

What is El Niño?

El Niño is associated with the weakening of easterly trade winds and the movement of warm water from the western Pacific toward the western coast of the Americas.

It’s the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters and atmospheric pressure in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

ENSO encompasses both the El Niño and La Niña phases, as well as a neutral phase, and has a significant influence on global temperatures and precipitation. What happens with the climate in the eastern Pacific ripples across the world, having an outsized impact on ecosystems, food supply and the broader global economy.

El Niño and La Niña usually fully develop between late summer and early autumn in the northern hemisphere until the following spring, but some events can last two years or longer. As mentioned, the La Niña phase that’s just finished spanned an extremely rare three years.

How El Niño develops

As we approach the peak of the expected El Niño phase in the next few months, we’ll also see a drop in atmospheric pressure across the tropical Pacific, with drier than average conditions in the Western Pacific and more rainfall and storms in the east, hitting Central America and South America’s western coast.

This pressure change then translates into global circulation, affecting seasonal weather over both Hemispheres.

El Niño tends to bring wetter weather to the Southern US, parts of Brazil and East and West Africa and drier conditions to India, Indonesia and Australia. It also tends to bring colder winters to Europe, which may have implications for natural gas prices this winter.

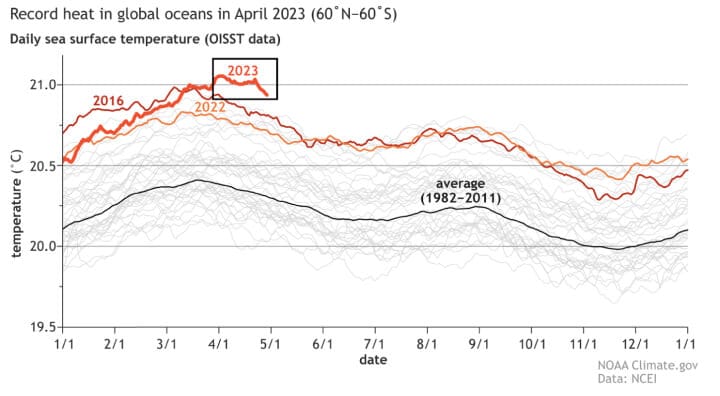

What’s unusual for El Niño this year is that the temperatures of the world’s oceans are already well above average (see figure below – the darkest line is 2023).

Usually, there’s a larger temperature contrast, but this year, the oceans are already at record highs, particularly the Northern Pacific and the North Atlantic. This is causing concern amongst climate scientists before El Niño has properly developed.

We’re entering uncharted territory with such a global configuration, and it’s almost impossible to forecast what this might mean with any real certainty. But we wouldn’t be surprised for this El Niño to break those global record temperatures from 2016 and all the serious implications for the global food supply that will entail.

The ‘ripple effect’

There are many positives to our diversified global food market, including mitigating the risks associated with extreme weather events in one growing region.

However, when there’s a strong global event like this season’s El Niño could be, the independence of distant breadbasket regions begins to break down.

A strong El Niño will mean a significant ripple effect across the global commodities complex, particularly softs like corn, wheat, oilseeds and equatorial softs like sugarcane, coffee, and cocoa.

According to recent Bloomberg Economics modelling, previous El Niños add an average of 3.9 percentage points to non-energy commodity prices. If this happens this season, it will further fuel the stubbornly high rates of global inflation.

Supporting higher prices

Generally, it will support higher prices in soft commodities because of the extreme weather it brings to crop-growing areas—for instance, drier conditions across Asia and Australia or heavier rains in parts of Brazil and Africa.

But it can also generate better crop yields in some regions like the U.S. Plains that enjoy the higher precipitation El Niño brings to the region.

A typical season also has a variable impact on the world’s oilseed production. It may support better canola or rapeseed yields in Canada but significantly less in Australia.

El Niño tends to bring favourable rains to the key soybean-growing regions in Brazil and Argentina, resulting in a higher output. And palm oil production could be negatively impacted in 2024 as Indonesia and Malaysia receive less rain this year, affecting next year’s harvest.

Collectively, the ENSO is estimated to affect yields on more than 25% of global croplands. Although that impact varies season by season, it can have a significant influence in the years when there’s a strong La Niña or El Niño phase relative to other global weather and climate patterns.

What El Niño will mean for softs?

We also expect El Niño to contribute to the market tightening for equatorial softs like sugarcane, coffee, and cocoa.

Raw sugar prices are already at relatively high historic levels, and heavy rain in Brazil or drought in India, Thailand, Australia and Central America could be problematic for sugar supplies, pushing those prices even higher.

Read our view on the tightening in global sugar markets.

Leading global cocoa-producing countries, Ivory Coast and Ghana, have been experiencing heavy rains this month, including flooding in key cocoa regions. That may be difficult to attribute to an emerging El Niño directly, but we know that it generally means heavier rainfall across the region.

In terms of coffee, we expect to see a more significant impact on the supply of the Robusta coffee variety popular in instant coffee products. The two biggest producers – Brazil and Vietnam – may see yields affected by extreme weather. Although we’ve not seen much effect so far, El Niño’s influence will be most keenly felt on production if we see an extended event into next year. As Robusta prices are already at generational highs, those prices will almost certainly be supported for the rest of 2023.

The more sensitive Arabica crop may not face as much impact unless El Niño persists longer than normal.

The biggest producers in Central and South America are currently experiencing relatively normal weather after three years of La Niña-induced drought, but crop yields may be impacted if El Niño keeps temperatures high into next year’s flowering and harvest.

Market expectations

How El Niño will develop this season isn’t clear, but soft commodities markets are already pricing in the expectation of its strength. We’re seeing potential supply concerns contributing to strong roll yields across the complex. If El Niño meets expectations, it’s also likely to add additional upward pressure to food price inflation.

The global economy is still struggling to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, grappling with the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict, high inflation and the risk of recession. Interest rate rises have proven to be relatively ineffectual in the face of a persistent inflationary environment for OECD countries, and there’s even less Central Banks and Governments can do about the weather.

There’s never a ‘right’ time for an extreme climate event, but this El Niño may be arriving at precisely the wrong time.